Copyright © 2010 David Schmidt

Chapter 1:

Grammars, trees, interpreters

- 1.1 Grammars (BNF)

- 1.1.1 Example: arithmetic expressions

- 1.1.2 Example: mini-command language

- 1.2 Operator trees

- 1.3 Semantics of operator trees

- 1.3.1 Semantics of expressions

- 1.3.2 Translating from one language to another

- 1.3.3 Semantics of commands: simplistic interpreter architecture

- 1.3.4 Simplistic commmand compiler

- 1.3.5 When to interpret? When to compile?

- 1.4 Parsing: How to construct an operator tree

- 1.4.1 Scanning: collecting words

- 1.4.2 Parsing expressions into operator trees

- 1.4.3 Parsing commands into operator trees

- 1.5 Why you should learn these techniques

When I speak to you, how do you understand what I am saying?

It is important that we communicate in a shared language, say,

English,

and it is important that I speak grammatically correctly

(e.g., ``Eaten house horse before.'' is an

incorrect, useless communication). Finally, you must know how

to attach meanings to the words and phrases that I use.

The same ideas are as important when you talk to a computer, by means of

a programming language:

the computer must ``know'' the

language you use. This includes:

-

syntax: the spelling and grammatical structure of the computer

language

-

semantics: the meanings of the language's words and phrases.

This chapter gives techniques for stating precisely a

language's syntax and semantics in terms of parser and interpreter

programs.

1.1 Grammars (BNF)

In the 1950s, Noam Chomsky realized that the syntax of a sentence

can be represented by a tree, and the rules

for building syntactically correct sentences can be written as an equational,

inductive definition. Chomsky called the definition a

grammar.

(John Backus and Peter Naur independently discovered the same concept,

and for this reason, a grammar is sometimes called

BNF (Backus-Naur form) notation.)

A grammar is a set of equations (rules),

where each equation defines

a set of phrases (strings of words).

The best way to learn this is by example.

1.1.1 Example: arithmetic expressions

Say we wish to define precisely how to write

arithmetic expressions, which consist

of numerals composed with addition and subtraction operators.

Here are the equations (rules)

that define the syntax of arithmetic expressions:

===================================================

EXPRESSION ::= NUMERAL | ( EXPRESSION OPERATOR EXPRESSION )

OPERATOR ::= + | -

NUMERAL is a sequence of digits from the set, {0,1,2,...,9}

===================================================

The words in upper-case letters (nonterminals)

name phrase and word forms:

an EXPRESSION phrase consists

of either a NUMERAL word

or

a left paren followed by another (smaller) EXPRESSION

phrase followed by an OPERATOR word

followed by another (smaller) EXPRESSION phrase

followed by a right paren.

(The vertical bar means ``or.'')

If the third equation is too informal for you, we can replace it with

these two:

NUMERAL ::= DIGIT | DIGIT NUMERAL

DIGIT ::= 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

but usually the spelling of individual words is stated informally,

like we did originally.

Using the rules, we can verify that this sequence of symbols is

a legal EXPRESSION phrase:

(4 - (3 + 2))

Here is the explanation, stated in words:

-

4 is a NUMERAL (as are 3 and 2)

-

all NUMERALs are legal EXPRESSION phrases, so (3 + 2) is an

EXPRESSION phrase, because + is an OPERATOR and 3 and 2 are EXPRESSIONS

-

(4 - (3 + 2)) is an EXPRESSION, because 4 and (3 + 2)

are EXPRESSIONs, and - is an OPERATOR.

Next, here is the justification, stated as a derivation,

where we calculate with the equations (rules) the phrase, (4 - (3 + 2)):

EXPRESSION => ( EXPRESSION OPERATOR EXPRESSION )

=> ( NUMERAL OPERATOR EXPRESSION )

=> (4 OPERATOR EXPRESSION)

=> (4 + EXPRESSION)

=> (4 + ( EXPRESSION OPERATOR EXPRESSION ))

=> (4 + ( NUMERAL OPERATOR EXPRESSION ))

=> (4 + ( 3 OPERATOR EXPRESSION ))

=> . . .

=> (4 + (3 - 2))

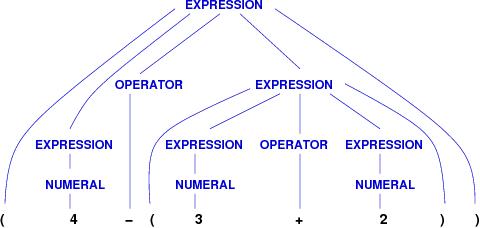

The derivation is compactly drawn

as a derivation tree:

===================================================

===================================================

===================================================

Indeed, a sequence of words is an EXPRESSION phrase if and only

if one can build a derivation tree for the words with the grammar rules.

In this way, we use grammars to define precisely the syntax of a language.

This is a crucial first step towards

building programs --- compilers and interpreters --- that read sentences

(programs) in the language and calculate their meanings (execute them).

Exercise: Write a derivation and derivation tree

for ((4 - 3) + 2). Why is 4 - 3 + 2 not a legal

EXPRESSION phrase?

1.1.2 Example: mini-command language

We can use a grammar to define the structure of an entire programming

language. Here is the grammar for a mini-programming language:

===================================================

PROGRAM ::= COMMANDLIST

COMMANDLIST ::= COMMAND | COMMAND ; COMMANDLIST

COMMAND ::= VAR = EXPRESSSION

| print VARIABLE

| while EXPRESSION : COMMANDLIST end

EXPRESSION ::= NUMERAL | VAR | ( EXPRESSION OPERATOR EXPRESSION )

OPERATOR ::= + | -

NUMERAL is a sequence of digits

VAR is a sequence of letters but not 'print', 'while', or 'end'

===================================================

The definition says that a program is a list (sequence) of commands,

which can be assignments or prints or while-loops. The body

of a while-loop is itself a list of commands.

The grammar does not explain what the phrases mean, so we have no information

that tells us

how a command like, while x : x = (x - 1) end,

operates --- this is an issue of semantics, which we consider

momentarily.

Exercise:

Draw the derivation trees for these PROGRAMs:

- x = (2 + x)

-

x = 3; print x

-

x = 3 ; while x : x = (x -1) end ; print x

1.2 Operator trees

A derivation tree shows the complete

internal structure of a sentence.

But the groupings of the words are what matter.

There is a useful way to format a derivation

tree so that the groupings are preserved

but the internal nonterminals are omitted.

This more compact representation is called

an operator tree or abstract-syntax tree

Here is the operator tree produced from the

derivation for (4 - (3 + 2)):

It is called an ``operator tree'' because the operators rest

in the places where the phrase names once appeared.

It's lots more compact than the original derivation tree,

but it has the same branching structure, which is the crucial part.

When we program with grammars and trees, we should

use a dynamic data-structures language, like Python or Scheme or Ruby or ML or Ocaml,

that lets us build nested lists. Then, we can represent an operator

tree as a nested list. Here is the nested-list representation

of the above operator tree:

["-", "4", ["+", "3", "2"]]

Here is a second example: For ((2+1) - (3-4)), we have this operator

tree (nested list):

["-", ["+", "2", "1"], ["-", "3", "4"]]

Finally, this program,

x = 3; while x : x = (x -1) end; print x,

has this operator tree:

[["=", "x", "3"],

["while", "x", [["=", "x", ["-", "x", "1"]]]],

["print", "x"]

]

(You can read it all on one line, if you wish:

[["=", "x", "3"], ["while", "x", [["=", "x", ["-", "x", "1"]]]], ["print", "x"]}.)

The COMMANDLIST is formatted as a list of command

operator trees.

List-based operator trees are easy for computer programs to use,

and we use them from here on.

Exercise: Draw operator trees for all the derivation

trees you have drawn in the previous exercises.

1.3 Semantics of operator trees

When a compiler or interpreter processes a computer program, it first builds the

program's operator tree. Then, it

calculates the meaning --- the semantics --- of the

tree.

The calculation of meaning is done by a recursively

defined tree-traversal function, just like the one you learned in CIS300.

Let's see how.

1.3.1 Semantics of expressions

An operator tree for arithmetic has two forms, which we can define

precisely with its own BNF rule, like this:

TREE ::= NUMERAL | [ OP, TREE, TREE ]

OP ::= + | -

NUMERAL ::= a string of digits

That is, every operator tree is either just a single numeral

or a list holding an operator symbol and two subtrees.

If we wish to traverse an operator tree and compute

its meaning,

we write a function that implements recursive calls

that match the recursion in the grammar rule.

The meaning of a binary operator tree is an integer.

For example, the tree,

["-", ["+", "2", "1"], ["-", "3", "4"]] computes to the integer, 4.

We

write a function, eval, that traverses an operator tree and computes

its numerical meaning. The eval function defines the

semantics (meaning) of the tree. eval is an interpreter

for the language of arithmetic.

The entire interpreter (written in Python)

looks like this --- it is just one single function that calls itself!

===================================================

def eval(t) :

"""pre: t is a TREE,

where TREE ::= NUMERAL | [ OP, TREE, TREE ]

OP ::= "+" | "-"

NUMERAL ::= a string of digits

post: ans is the numerical meaning of t

returns: ans

"""

if isinstance(t, str) and t.isdigit() : # is t a string holding an int?

ans = int(t) # cast the string to an int

else : # t is a list, [op, t1, t2]

op = t[0]

t1 = t[1]

t2 = t[2]

ans1 = eval(t1)

# assert: ans1 is the numerical meaning of t1

ans2 = eval(t2)

# assert: ans2 is the numerical meaning of t2

if op == "+" :

ans = ans1 + ans2

elif op == "-" :

ans = ans1 - ans2

else : # something's wrong with argument t !

print "eval error:", t, "is illegal"

raise Exception # stops the program

return ans

===================================================

The function's recursions match exactly the recursions in the grammar

rule that defines the set of operator trees.

The recursion computes the numerical meanings

of the subtrees and combines them to get the meaning of

the complete tree.

Exercise: Copy the function into a file named

eval.py, and start Python on it:

python -i eval.py. Call the function:

eval( ["-", ["+", "2", "1"], ["-", "3", "4"]] ).

Try more examples.

Here is a sketch of the execution of

eval(["-", ["+", "2", "1"], ["-", "3", "4"]]),

which computes to 3 - (-1) = 4.

In the sketch,

each time eval is called, we copy freshly its body, to mimick how a computer

creates a new activation record;

the way we write this is called

copy-rule semantics. A copy-rule semantics

shows the expansion and contraction of the computer's

activation-record stack:

===================================================

eval( ["-", ["+", "2", "1"], ["-", "3", "4"]] )

=> op = "-"

t1 = ["+", "2", "1"]

t2 = ["-", "3", "4"]

ans1 = eval(t1) => op = "+"

t1 = "2"

t2 = "1"

ans1 = eval(t1) => ans = 2

= 2

ans2 = eval(t2) => ans = 1

= 1

ans = 2+1 = 3

= 3

ans2 = eval(t2) => op = "-"

t1 = "3"

t2 = "4"

ans1 = eval(t1) => ans = 3

= 3

ans2 = eval(t2) => ans = 4

= 4

ans = 3-4 = -1

= -1

ans = 3 - (-1) = 4

= 4

===================================================

Each => represents a recursive call (restart)

of eval on a subtree of the original

operator tree. Each restart keeps its own namespace

of its local variables, which it uses to compute the answer for its subtree.

Eventually, the answers are returned and combined.

The pattern of calls to eval matches

the pattern of structure in the original operator tree.

1.3.2 Translating from one language to another

A compiler (translator) is a program that

converts a program into an operator tree and then converts the

operator tree into a program in a new programming language

(e.g., machine language). Think about a compiler for C, which

translates C programs into machine language.

We use the same technique shown above to compile

an operator tree into its

postfix-string representation, which these days is called

``byte code.'' This is essentially what a Java compiler does ---

translates Java programs into byte code:

===================================================

def postfix(t) :

"""pre: t is a TREE, where TREE ::= NUM | [ OP, TREE, TREE ]

post: ans is a string holding a postfix (operator-last) sequence

of the symbols within t

returns: ans

"""

if isinstance(t, str) and t.isdigit() : # is t a string holding an int?

ans = t #(*) the postfix of a NUM is just the NUM itself

else : # t is a list, [op, t1, t2]

op = t[0]

t1 = t[1]

t2 = t[2]

ans1 = postfix(t1)

# assert: ans1 is a string holding the postfix form of t1

ans2 = postfix(t2)

# assert: ans2 is a string holding the postfix form of t2

# concatenate the subanswers into one string:

if op == "+" :

ans = ans1 + ans2 + "+" #(*)

elif op == "-" :

ans = ans1 + ans2 + "-" #(*)

else :

print "error:", t, "is illegal"

raise Exception # stops the program

return ans

===================================================

This code is exactly the code for eval, but at the positions marked

#(*), where meanings were formerly computed, now a postfix string

is constructed instead.

For example, postfix(["+", ["-", "2", "1"], "4"]) builds the postfix

string, "21-4+". The string states what to compute, in postfix style.

We draw the computation like

this:

===================================================

postfix(["+", ["-", "2", "1"], "4"])

=> op = "+"

t1 = ["-", "2", "1"]

t2 = "4"

ans1 = postfix(t1) => op = "-"

t1 = "2"

t2 = "1"

ans1 = postfix(t1) => ans = "2"

= "2"

ans2 = postfix(t2) => ans = "1"

= "1"

ans = "2" + "1" + "-"

= "21-"

= "21-"

ans2 = postfix(t2) => ans = "4"

= "4"

ans = "21-" + "4" + "+"

= "21-4+"

===================================================

Again,

each => represents a recursive call (restart)

of postfix on a subtree of the original

operator tree.

If the previous explanation was not enough for you, you can

insert print commands into postfix so that the computer

shows you the path it takes to translate the tree:

===================================================

def postfixx(level, t) :

"""pre: t is a TREE, where TREE ::= INT | [ OP, TREE, TREE ]

level is an int, indicating at what depth t is situated

in the overall tree being postfixed

post: ans is a string holding a postfix (operator-last) sequence

of the symbols within t

returns: ans

"""

print level * " ", "Entering subtree t=", t

if isinstance(t, str) : # is t a numeral?

ans = str(t)

else : # t is a list, [op, t1, t2]

op = t[0]

t1 = t[1]

t2 = t[2]

ans1 = postfixx(level + 1, t1)

ans2 = postfixx(level + 1, t2)

ans = ans1 + ans2 + op # the answer combines the two subanswers

print level * " ", "Exiting subtree t=", t, " ans=", ans

print

return ans

===================================================

If you use Python and call this function, say, postfixx(0, ["+", "2" , ["-", "3" , "4"]]),

you will see this printout:

===================================================

Entering subtree t= ['+', '2', ['-', '3', '4']]

Entering subtree t= 2

Exiting subtree t= 2 ans= 2

Entering subtree t= ['-', '3', '4']

Entering subtree t= 3

Exiting subtree t= 3 ans= 3

Entering subtree t= 4

Exiting subtree t= 4 ans= 4

Exiting subtree t= ['-', '3', '4'] ans= 34-

Exiting subtree t= ['+', '2', ['-', '3', '4']] ans= 234-+

===================================================

The computer descended into the levels of the tree

from left to right, computing answers for its leaves that were combined

into an answer for the entire tree.

1.3.3 Semantics of commands: simplistic interpreter architecture

We can use the techniques from the previous section

to give semantics to a real programming language.

Here again is the grammar for the mini-programming

language:

===================================================

PROGRAM ::= COMMANDLIST

COMMANDLIST ::= COMMAND | COMMAND ; COMMANDLIST

COMMAND ::= VAR = EXPRESSSION

| print VARIABLE

| while EXPRESSION : COMMANDLIST end

EXPRESSION ::= NUMERAL | VAR | ( EXPRESSION OPERATOR EXPRESSION )

OPERATOR is + or -

NUMERAL is a sequence of digits from the set, {0,1,2,...,9}

VAR is a string beginning with a letter; it cannot be 'print', 'while', or 'end'

===================================================

For program,

x = 3 ; while x : x = x - 1 end ; print x

here is its operator tree:

[["=", "x", "3"],

["while", "x", [["=", "x", ["-", "x", "1"]]]],

["print", "x"]

]

The operator tree has a commandlist level,

a command level, and an

expression level. A program is just a commandlist.

Here is the grammar of the operator trees:

PTREE ::= CLIST

CLIST ::= [ CTREE+ ]

where CTREE+ means one or more CTREEs

CTREE ::= ["=", VAR, ETREE] | ["print", VAR] | ["while", ETREE, CLIST]

ETREE ::= NUMERAL | VAR | [OP, ETREE, ETREE]

where OP is either "+" or "-"

So, we write four interpreter functions (why?),

and the

functions define

the semantics of the computer language.

It is just like the interpreters that underlie

the implementations of Python and Java.

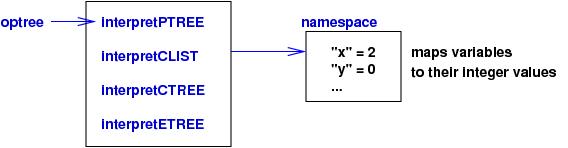

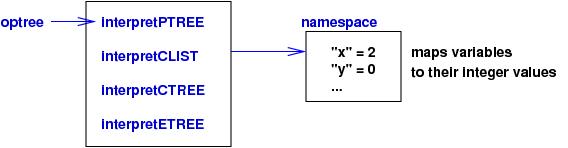

The interpreter's

architecture can be drawn like this, where the arrows

denote flow of input data and flow of

calls to data structures:

Here is the coding of the data structures and

functions, in Python:

===================================================

"""Interpreter for a mini-language with variables and loops.

There is one crucial data structure:

"""

ns = {} # ns is a namespace --- it holds the program's variable names

# and their values. It is a Python hash table (dictionary).

# For example, if

# ns = {'x'= 2, 'y' = 0}, then variable x names int 2

# and variable y names int 0.

def interpretCLIST(p) :

"""pre: p is a program represented as a CLIST ::= [ CTREE+ ]

where CTREE+ means one or more CTREEs

post: ns holds all the updates commanded by program p

"""

for command in p :

interpretCTREE(command)

def interpretCTREE(c) :

"""pre: c is a command represented as a CTREE:

CTREE ::= ["=", VAR, ETREE] | ["print", VAR] | ["while", ETREE, CLIST]

post: ns holds all the updates commanded by c

"""

operator = c[0]

if operator == "=" : # assignment command, ["=", VAR, ETREE]

var = c[1] # get left-hand side

exprval = interpretETREE(c[2]) # evaluate the right-hand side

ns[var] = exprval # do the assignment

elif operator == "print" : # print command, ["print", VAR]

var = c[1]

if var in ns : # see if variable name is defined

ans = ns[var] # look up its value

print ans

else :

crash("variable name undefined")

elif operator == "while" : # while command

expr = c[1]

body = c[2]

while (interpretETREE(expr) != 0) :

interpretCLIST(body)

else : # error

crash("invalid command")

def interpretETREE(e) :

"""pre: e is an expression represented as an ETREE:

ETREE ::= NUMERAL | VAR | [OP, ETREE, ETREE]

where OP is either "+" or "-"

post: ans holds the numerical value of e

returns: ans

"""

if isinstance(e, str) and e.isdigit() : # a numeral

ans = int(e)

elif isinstance(e, str) and len(e) > 0 and e[0].isalpha() : # var name

if e in ns : # see if variable name is defined

ans = ns[e] # look up its value

else :

crash("variable name undefined")

else : # [op, e1, e2]

op = e[0]

ans1 = interpretETREE(e[1])

ans2 = interpretETREE(e[2])

if op == "+" :

ans = ans1 + ans2

elif op == "-" :

ans = ans1 - ans2

else :

crash("illegal arithmetic operator")

return ans

def crash(message) :

"""pre: message is a string

post: message is printed and interpreter stopped

"""

print message + "! crash! core dump: ", ns

raise Exception # stops the interpreter

def main(program) :

"""pre: program is a PTREE ::= CLIST

post: ns holds all updates within program

"""

global ns # ns is global to main

ns = {}

interpretCLIST(program)

print "final namespace =", ns

===================================================

The main function starts the interpreter:

main([["=", "x", "3"],

["while", "x", [["=", "x", ["-", "x", "1"]], ["print", "x"]]],

])

This program

assigns 3 to "x";

decrements "x"'s value to 2 to 1 to 0;

prints each decrement;

then stops the loop.

Exercise: install and test the interpreter.

Another name for the interpreter is a virtual machine,

because the interpreter adapts the computer hardware we have

into a machine that understands the instruction set of a new language.

1.3.4 Simplistic commmand compiler

Perhaps a program with commands must be translated into a language

that a specific processor understands. This is the case with Java,

which must be translated into a language called byte code,

that is a machine-language variant easily understood by a wide range

of processor chips.

As we saw in the section on postfix expressions, we can revise the

interpreter for commands so that it generates a compiled program.

Here is the command interpreter revised the same way that we did earlier

to generate

postfix expressions:

===================================================

"""Compiler for a mini-language with variables and loops.

Translates a program into byte code containing these instructions:

LOADNUM n

LOAD v

ADD

SUBTRACT

STORE v

PRINT v

IFZERO EXITLOOP

BEGINLOOP

ENDLOOP

"""

symboltable = [] # list of variable names that will be stored in runtime memory;

# used for simple "declaration checking" of the program

def compileCLIST(p) :

"""pre: p is a program represented as a CLIST ::= [ CTREE+ ]

where CTREE+ means one or more CTREEs

post: ans holds the compiled byte code for p

returns: ans

"""

ans = ""

for command in p :

ans = ans + compileCTREE(command)

return ans

def compileCTREE(c) :

"""pre: c is a command represented as a CTREE:

CTREE ::= ["=", VAR, ETREE] | ["print", VAR] | ["while", ETREE, CLIST]

post: ans is a string that holds the compiled byte code for c

returns: ans

"""

operator = c[0]

if operator == "=" : # assignment command, ["=", VAR, ETREE]

var = c[1] # get left-hand side

exprcode = compileETREE(c[2])

symboltable.append(var) # remember the var in the symboltable list

ans = exprcode + "STORE " + var + "\n"

elif operator == "print" : # print command, ["print", VAR]

var = c[1]

if var in symboltable : # see if variable name is defined

ans = "PRINT " + var + "\n"

else :

crash("variable name undefined")

elif operator == "while" : # while command

expr = c[1]

body = c[2]

exprcode = compileETREE(c[1])

bodycode = compileETREE(c[2])

ans = "BEGINLOOP \n" + exprcode \

+ "IFZERO EXITLOOP \n" + bodycode + "ENDLOOP \n"

else : # error

crash("invalid command")

return ans

def compileETREE(e) :

"""pre: e is an expression represented as an ETREE:

ETREE ::= NUMERAL | VAR | [OP, ETREE, ETREE]

where OP is either "+" or "-"

post: ans is a string that holds the compiled byte code for e

returns: ans

"""

if isinstance(e, str) and e.isdigit() : # a numeral

ans = "LOADNUM " + e + "\n"

elif isinstance(e, str) and len(e) > 0 and e[0].isalpha() : # var name

if e in symboltable : # see if variable name is defined

ans = "LOAD " + e + "\n"

else :

crash("variable name undefined")

else : # [op, e1, e2]

op = e[0]

ans1 = compileETREE(e[1])

ans2 = compileETREE(e[2])

if op == "+" :

ans = ans1 + ans2 + "ADD \n"

elif op == "-" :

ans = ans1 - ans2 + "SUBTRACT \n"

else :

crash("illegal arithmetic operator")

return ans

def crash(message) :

"""pre: message is a string

post: message is printed and interpreter stopped

"""

print message + "! crash!", symboltable

raise Exception # stops the interpreter

def main(program) :

"""pre: program is a PTREE ::= CLIST

post: code holds the compiled byte code for program

"""

global symboltable # ns is global to main

symboltable = []

code = compileCLIST(program)

print code

===================================================

For example, the program,

x = 2; y = (x + 1); print y,

would be compiled by the main function like this:

main([['=','x','2'], ['=','y',['+','x','1']], ['print','y']])

LOADNUM 2

STORE x

LOAD x

LOADNUM 1

ADD

STORE y

PRINT y

The compiler traversed the operator tree and translated its meaning

into a sequence of byte-code instructions that can be executed

by a processor that understands byte code.

There is a small but important technical point to notice:

The original interpreter collected all the assignments within

a namespace structure, ns. But when we compile a program,

the assignments are not done by the compiler, but by the machine

that executes the bytecode. For this reason, ns is removed from

the compiler. But in its place, there is a new structure,

symboltable, that remembers which variables might be created

and assigned when the byte-code program executes.

The symboltable

is a kind of ``ghost'' that foreshadows the run-time memory, and it

keeps track of variable declarations and can help spot illegal uses

of variables. In this way, the compiler can print error messages that

indicate when the program will fail at run-time.

(If the command language contained declaration statements with data types,

this information would be saved in symboltable and used to type check

the program's commands during the translation process.)

Finally, note that the byte code generated for while-loops is overly

simplistic --- a real-life compiler would generate jump commands and

labels when translating a loop.

For example,

x = 2; while x : x = x - 1; print x

compiles to where a realistic compiler produces this:

LOADNUM 2 LOADNUM 2

STORE x STORE x

BEGINLOOP LABEL1:

LOAD x LOAD x

IFZERO EXITLOOP JUMPZERO LABEL2

LOAD x LOAD x

LOADNUM 1 LOADNUM 1

SUBTRACT SUBTRACT

STORE x STORE x

ENDLOOP JUMP LABEL1

PRINT x LABEL2:

PRINT x

We have omitted label generation to keep the compiler

small and simple.

1.3.5 When to interpret? When to compile?

When you design a new language, you always write an interpreter

first, so that you can understand the language's semantics.

If time-and-space performance requirements are critical,

revise the interpreter into a compiler: The compiler does

the tedious steps of operator-tree traversal/disassembly, and it performs

the routine tests related to variable declarations, expression

compatibilities, etc. This leaves only the primitive computation steps

that must be translated into the compiled code. The result will be a smaller,

faster program to execute.

If the hardware you must use does not understand the language you

used to write the interpreter, revise the interpreter to be a compiler

that emits a program in a language understood by the hardware.

(Or, can you rewrite the interpreter in a language the hardware

understands? This would be easier.)

If the program must be placed in firmware or burned into a chip,

make the interpreter into a compiler so that the process of

operator-tree disassembly can be done once and for all and need

not be included in the code placed in the firmware/chip.

If program correctness is critical, stay with the interpreter ---

It is easier to analyze and prove an interpreter correct

that it is a compiler.

If the language will be repeatedly revised or extended, stay with the

interpreter. Revising compilers is a nightmare job.

1.4 Parsing: How to construct an operator tree

Because operator trees are processed so easily by recursively

defined functions, it is best to write a program that

reads the input text program and builds

the operator tree straightaway. (The derivation tree itself is never built!)

This activity is called parsing.

The compiler or interpreter for every programming language does

parsing before it does translation or interpretation.

For example, say we want a program, parseExpr, that can read

a line of text, like ((2+1) - (3 - 4) ),

and build the operator tree,

["-", ["+", "2", "1"], ["-", "3", "4"]].

The program's algorithm will go like this:

-

Separate the symbols in the text line into their individual

operators and words, discarding blanks. Make a list of the words.

-

Read the words in the list one by one, using the

grammar rules to guide building the operator tree.

The second step looks like a serious challenge, but we

can use the same technique seen in the previous section:

we write a family of functions, one per grammar rule, that

reads the words and builds the tree. This technique is

called recursive-descent parsing.

1.4.1 Scanning: collecting words

For the first step, here is a little function that disassembles

a line of text and makes a list of words that were found in the text:

===================================================

def scan(text) :

"""scan splits apart the symbols in text into a list.

pre: text is a string holding a program phrase

post: answer is a list of the words and symbols within text

(spaces and newlines are removed)

"""

OPERATORS = ("(", ")", "+", "-", ";", ":", "=") # must be one-symbol operators

SPACES = (" ", "\n")

SEPARATORS = OPERATORS + SPACES

nextword = "" # the next symbol/word to be added to the answer list

answer = []

for letter in text:

# invariant: answer + nextword + letter equals all the words/symbols

# read so far from text with SPACES removed

# see if nextword is complete and should be appended to answer:

if letter in SEPARATORS and nextword != "" :

answer.append(nextword)

nextword = ""

if letter in OPERATORS :

answer.append(letter)

elif letter in SPACES :

pass # discard space

else : # build a word or numeral

nextword = nextword + letter

if nextword != "" :

answer.append(nextword)

return answer

===================================================

For example, scan("((2+1) - (3 - 4) )") returns as its answer,

['(', '(', '2', '+', '1', ')', '-', '(', '3', '-', '4', ')', ')'].

1.4.2 Parsing expressions into operator trees

Now, we use the grammar rule to guide writing the

function that reads the list of words and constructs the operator tree.

Here is the grammar rule for arithmetic expressions:

EXPRESSION ::= NUMERAL | VAR | ( EXPRESSION OPERATOR EXPRESSION )

where OPERATOR is "+" or "-"

NUMERAL is a sequence of digits

VAR is a string of letters

For each construction in the grammar rule,

there is an operator tree to build:

for NUMERAL, the tree is NUMERAL

for VAR, the tree is VAR

for ( EXPRESSION1 OPERATOR EXPRESSION2 ), the tree is [OPERATOR, T1, T2]

where T1 is the tree for EXPRESSION1

T2 is the tree for EXPRESSION2

We write a function, parseEXPR, that reads the words of an arithmetic

expression and builds the tree, based on the words. Like the eval function

seen earlier, the grammar rules show us what to do.

It is simplest to use these global variables and a helper function

to parcel out the input words one at a time:

===================================================

# say that inputtext holds the text that we must parse into a tree:

wordlist = scan(inputtext) # holds the remaining unread words

nextword = "" # holds the first unread word

# global invariant: nextword + wordlist == all remaining unread words

EOF = "!" # a word that marks the end of the input words

getNextword() # call this function to move the first word into nextword:

def getNextword() :

"""moves the front word in wordlist to nextword.

If wordlist is empty, sets nextword = EOF

"""

global nextword, wordlist

if wordlist == [] :

nextword = EOF

else :

nextword = wordlist[0]

wordlist = wordlist[1:]

===================================================

The function that builds expression-operator trees looks like this:

===================================================

def parseEXPR() :

"""builds an EXPR operator tree from the words in nextword + wordlist,

where EXPR ::= NUMERAL | VAR | ( EXPR OP EXPR )

OP is "+" or "-"

also, maintains the global invariant (on wordlist and nextword)

"""

if nextword.isdigit() : # a NUMERAL ?

ans = nextword

getNextword()

elif isVar(nextword) : # a VARIABLE ?

ans = nextword

getNextword()

elif nextword == "(" : # ( EXPR op EXPR ) ?

getNextword()

tree1 = parseEXPR()

op = nextword

if op == "+" or op == "-" :

getNextword()

tree2 = parseEXPR()

if nextword == ")" :

ans = [op, tree1, tree2]

getNextword()

else :

error("missing )")

else :

error("missing operator")

else :

error("illegal symbol to start an expression")

return ans

def isVar(word) :

"""checks whether word is a legal variable name"""

KEYWORDS = ("print", "while", "end")

ans = ( word.isalpha() and not(word in KEYWORDS) )

return ans

def error(message) :

"""prints an error message and halts the parse"""

print "parse error: " + message

print nextword, wordlist

raise Exception

===================================================

Function parseEXPR uses the grammar rule to ask the appropriate questions

about nextword, the next input word, to decide which form of operator

tree to build. It is not an accident that the grammar rule for

EXPRESSION is defined so that each of the three choices for an expresion

begins with a unique word/symbol. This is the key to

choosing the appropriate form of tree to build.

We tie the pieces together like this:

===================================================

# global invariant: nextword + wordlist == all remaining unread words

nextword = "" # holds the first unread word

wordlist = [] # holds the remaining unread words

EOF = "!" # a word that marks the end of the input words

def main() :

global wordlist

# read the input text, break into words, and place into wordlist:

text = raw_input("Type an arithmetic expression: ")

wordlist = scan(text)

# do the parse:

getNextword()

tree = parseEXPR()

print tree

if nextword != EOF :

error("there are extra words")

===================================================

1.4.3 Parsing commands into operator trees

We can use the above functions to build a parser for the mini-programming

language. Using the same technique, we make functions that parse

commands and lists of commands:

===================================================

def parseCOMMAND() :

"""builds a COMMAND operator tree from the words in nextword + wordlist,

where COMMAND ::= VAR = EXPRESSSION

| print VARIABLE

| while EXPRESSION : COMMANDLIST end

also, maintains the global invariant (on wordlist and nextword)

"""

if nextword == "print" : # print VARIABLE ?

getNextword()

if isVar(nextword) :

ans = ["print", nextword]

getNextword()

else :

error("expected var")

elif nextword == "while" : # while EXPRESSION : COMMANDLIST end ?

getNextword()

exprtree = parseEXPR()

if nextword == ":" :

getNextword()

else :

error("missing :")

cmdlisttree = parseCMDLIST()

if nextword == "end" :

ans = ["while", exprtree, cmdlisttree]

getNextword()

else :

error("missing end")

elif isVar(nextword) : # VARIABLE = EXPRESSION ?

v = nextword

getNextword()

if nextword == "=" :

getNextword()

exprtree = parseEXPR()

ans = ["=", v, exprtree]

else :

error("missing =")

else : # error -- bad command

error("bad word to start a command")

return ans

===================================================

We finish with the function that collects the commands in a COMMANDLIST:

===================================================

def parseCMDLIST() :

"""builds a COMMANDLIST tree from the words in nextword + wordlist,

where COMMANDLIST ::= COMMAND | COMMAND ; COMMANDLIST

that is, one or more COMMANDS, separated by ;s

also, maintains the global invariant (on wordlist and nextword)

"""

anslist = [ parseCOMMAND() ] # parse first command

while nextword == ";" : # collect any other COMMANDS

getNextword()

anslist.append( parseCOMMAND() )

return anslist

def main() :

"""reads the input mini-program and builds an operator tree for it,

where PROGRAM ::= COMMANDLIST

Initializes the global invariant (for nextword and wordlist)

"""

global wordlist

text = raw_input("Type the program: ")

wordlist = scan(text)

getNextword()

# assert: invariant for nextword and wordlist holds true here

tree = parseCMDLIST()

# assert: tree holds the entire operator tree for text

print tree

if nextword != EOF :

error("there are extra words")

===================================================

This style of parsing is also called top-down, predictive

parsing because it constructs the operator tree from the root

at the tree's top downwards towards the leaves, predicting the

correct structure by looking at the words in the input program,

one at a time. You can see how important it is to have exactly

the correct number of keywords and brackets at the exactly

correct positions in the input program so that this technique

will succeed. Parsing theory is the study of

how to write grammars and parsers successfully.

Once you have mastered writing parsers by hand, you realize that

the process is almost completely mechanical --- starting from the

grammar definition, you mechanically write the correct code.

Now, you are ready to use a tool called a parser generator

to do the code writing for you: The input to a parser generator

is the set of grammar rules and the output is the parser.

Yacc is a well known parser generator, and

PLY is a version of Yacc coded to work with Python.

Antlr is another popular parser generator.

Exercise: Copy the scanner and parser into one file

and the command interpreter into another. In a third file, write

a driver program that reads a source program and then imports and

calls the scanner-parser and interpreter modules.

Exercise: Add an if-else command to the

parser and interpreter.

Exercise: Add parameterless procedures to the language:

COMMAND ::= . . . | proc I : C | call I

In the interpreter, save the body of a newly defined procedure

in the namespace. (That is, the semantics of

proc I: C is similar to I = C.) What is the semantics of

call I? Implement this.

1.5 Why you should learn these techniques

Anyone who uses a programming language should know the rules

for writing syntactically legal programs. The rules are

the grammar. Anyone who writes a program should know what the

program means, what it is intended to do. This requires study

of the language's semantics. Most languages have ``documentation''

written in a stilted English, peppered with examples. Sometimes,

this documentation is well-enough written to answer your questions

about what the language's constructions mean. But sometimes,

a person must peer inside the language's definitional interpreter,

which is written like the ones in this chapter, to see what a construction

means.

Someday, you will be asked to design a language of your own.

Indeed, this happens each time you design a piece of software,

because the inputs to the software must arrive in a sensible

order --- syntax --- for the software to process them.

Software used by humans requires an input language so that

a human knows the rules (grammar) for communicating with the software.

Sometimes, the grammar is just a matter of the order of mouse drags

and clicks; this is a kind of point-and-shove language that a human

might use to another human when the two people are unwilling to speak

words to each other.

But when a human wishes to speak (type) words to a program, a real

language of words, phrases, and sentences is required. What should

this language look like? What operations, data, control are needed

within it? When a GUI must map a sequence of mouse drags and clicks

into target code, what kind of code should it generate?

If you are designing a piece of software, you must design its input

language, and you must write the parser and the interpreter

for the language. This is why we must learn the technques in this

chapter and this course.

Programming languages that are designed to solve problems in some

specialty area (e.g., avionics, telecommunications, word processing,

database access, game playing) must have operations that are tailored

to the specialty area and must have data and control structures

that support the forms of computation in the area. A language

oriented towards a specialty area is called a domain-specific

programming language. By the end of this course, you will have

basic skills to design such languages.

By the way, grammar (BNF) notation is a domain-specific programming language ---

for writing parser programs! There are automated systems

(Yacc, PLY, Antlr, Bison, ...) that can read a grammar definition

and automatically write the parser code that we wrote by hand in this

chapter. So, when you write a grammar, you have, for all practical

purposes, already written its parser --- what's left to

do is purely mechanical.

===================================================